WPRB and Me—Perfect Together!

By Sean Murphy ’94 [photo: Nicole Scheller]

I’m definitely not the first, and I hope I’m not the last, to be able to say that I majored in WPRB. Officially, I graduated with a degree in Politics, but my independent work and thesis focused on regulatory processes at the Federal Communications Commission. And that work resulted from many long and late nights spent playing and talking about records and bands and radio and what it meant to be non-profit, commercial, and independent all at the same time. From the music to the management lessons to the friendships, my WPRB experiences still reverberate nearly 25 years later.

I arrived at the basement of Holder Hall’s 11th entry in September 1990. I had some idea of what I might be getting into, as I’d spent the previous spring and summer interning at WMBR, 88.1 Cambridge, MA (MIT’s radio station). WPRB was different, from the rigidity of the program logs and actual paid 30- and 60-second ads to the presence of the main record library right in the control room. But the most important similarity was that WPRB saw and understood itself as an institution at, but not of, the university.

I became the tech director in the second semester of my freshman year, largely because I had used a soldering iron at some point before I first arrived at the station. I learned of my election/conscription through a note scrawled on the back of a pizza box that was left in front of my dorm room — the Senior Board at the time used to pick up all the new board members, but I wasn’t home that night. Becoming program director for 1992 and station manager for 1993 were far less dramatic but substantially more time-consuming.

My first solo graveyard (late night show) was the same night in January 1991 that Operation Desert Storm began. I don’t have any airchecks or playlists, but I do remember playing both Black Sabbath’s “War Pigs” and The Cure’s “Fire in Cairo” as vaguely “topical” selections.

The summer of 1991 was a major turning point in the station’s history — the completion of a seven-year project to move WPRB’s transmission facilities from Holder Tower to the NJ Public Television site at Baker’s Basin. Despite an apparent loss of broadcast power output (17,000 watts at Holder, but only 14,000 watts at Baker’s Basin), the increased height of our broadcast antenna at Baker’s Basin resulted in a broadcast signal with twice the effective radius. For the entire fall of 1991, we kept a map of New Jersey and eastern Pennsylvania on the door of Control A, highlighting each new town or city that would check in with us or make a request. By the time the colors faded, we’d colored in three-quarters of New Jersey and most of Philadelphia and its suburban counties. We even toyed with a slogan advertising our broadcast range as “from Newark to Newark” — when driving north on I-95, the signal started to come in just past Newark, Delaware and died out just before Newark (Liberty) International Airport.

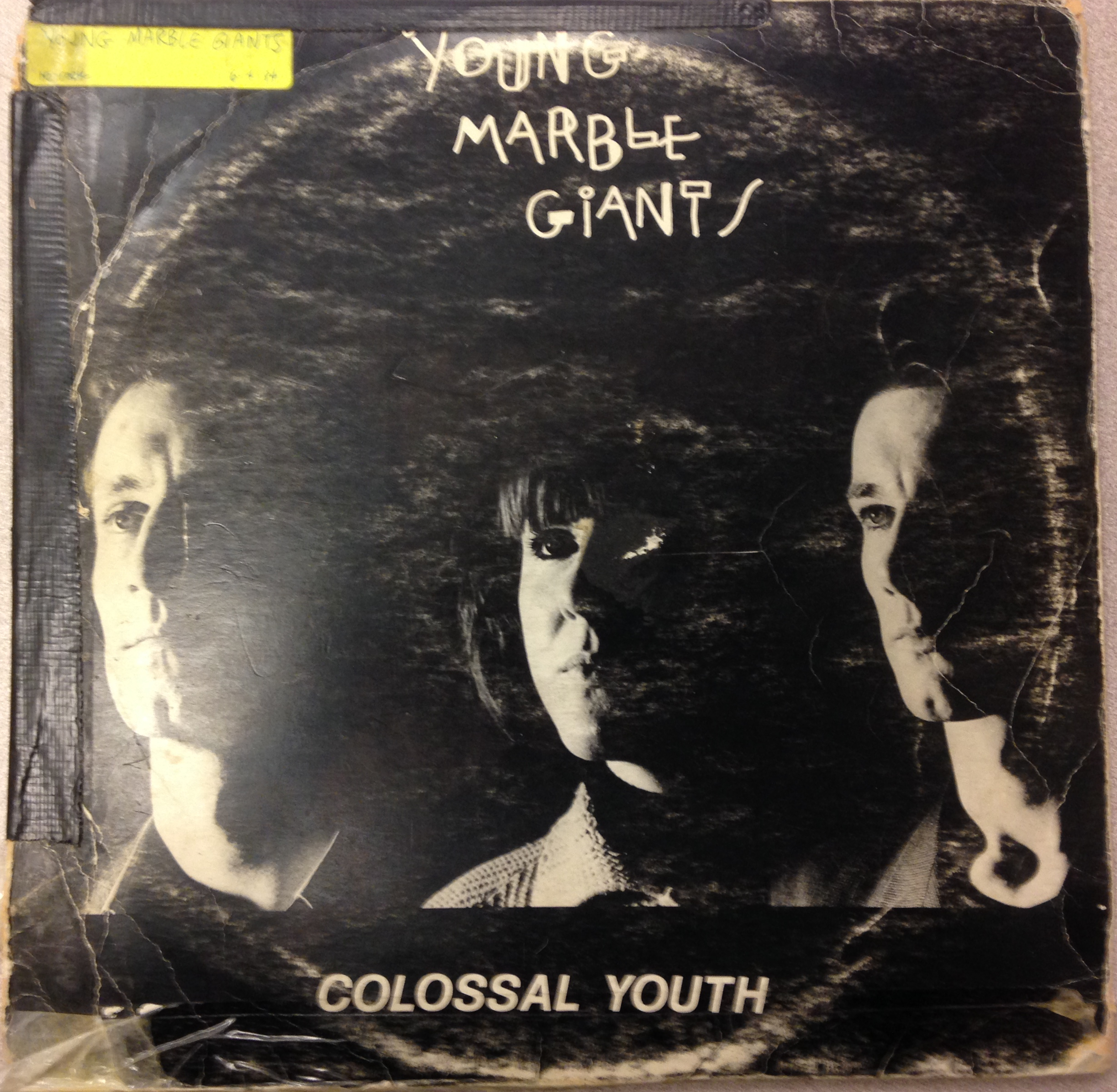

The signal boost changed the station’s profile in many ways. The management at 103.5 FM in New York City (who had paid for WPRB’s upgrade as part of their own transmitter / antenna relocation) sent out helicopters with electromagnetic field strength meters, suspecting that WPRB must have done something wrong in its upgrade. I made the decision to abandon “Old Nassau” as the music bed for WPRB’s sign-on and sign-off announcements, opting for Vince Guaraldi’s “Linus and Lucy” in the morning and evening before later adopting Young Marble Giant’s “Wind in the Rigging” as the sign-off.

LISTEN: Sean voices the “Linus & Lucy” Sign-On Message

LISTEN: Sean voices the Young Marble Giants Sign-Off Message

(One of my favorite late-night radio tricks was to nail the segue from the static at the end of that song to the static produced when WPRB shut down the transmitter.) We received numerous phone calls throughout 1992 from north-central New Jersey complaining about how “Linus and Lucy” became an unofficial (and unwelcome) alarm clock — when WPRB turned on its transmitter each morning, our signal interfered with or drowned out the New York City country music station at 103.5FM. In a welcome reduction of WPRB’s reach, the air signal no longer bled into phone lines and toasters around campus. And every musician touring on the east coast knew that they could turn off their mix tapes and tune in to WPRB anywhere between New York City and Wilmington.

I’ve lost count of the number of nights many of us spent at the Khyber Pass in Philly as “roadies” for one band or another, with the booking agent turning a blind eye to our ages (as long as we stayed away from the bar). But I do recall my reactions whenever someone would introduce themselves to me at the Khyber or Maxwell’s after recognizing my voice from the radio — a strange mix of pride and excitement and embarrassment.

Although I was primarily a “rock” DJ, I had to do a little of everything while serving as program director and station manager. Two non-traditional shows stand out in my memory: trying to kill Sunday Opera, and covering for (hip-hop show) The Raw Deal.

Sunday Opera was a bit like pre-hipster brussels sprouts — successive program directors always acknowledged that it was a “good thing” to have on the schedule, but it was an acquired taste for many DJs. I drew the short straw to program Sunday Opera one summer, surviving the stuffy, dank afternoons by listening to other records through the control board’s “audition” channel while the opera was in the “program” channel. I had no real interest in the pieces I was playing, aside from one modern opera that included a tenor singing out “you motherfucker” (nobody flagged it as inappropriate for airplay — shocked the daylights out of me!) I’d occasionally get phone calls from listeners who heard (or claimed to hear) some bleed-through or were upset about skips in the album. But the worst was an old woman who shrieked at me about my failed attempts to pronounce some German name or title, and then hung up before I could even apologize for my lack of knowledge.

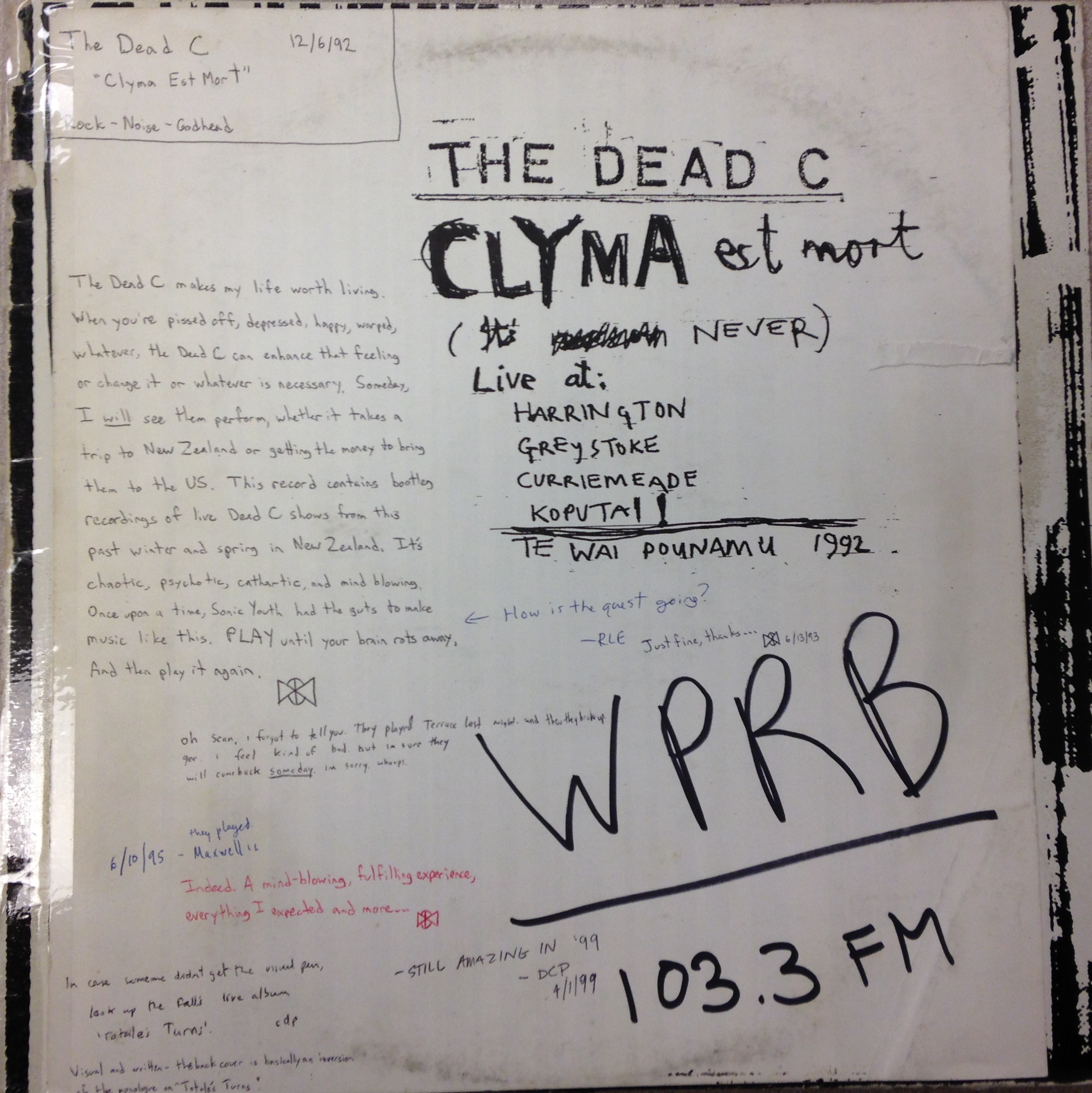

My thoroughly spiteful response was to remove Sunday Opera from the schedule starting the following week. But for that first week, I kept up the pretense of playing opera — specifically “The Dead Sea Opera” composed by “Matthew Shawkey.” The three-hour broadcast consisted of my playing at least two records or CDs at all times, sometimes at the wrong speeds or backwards, with a focus on the droning, “post-apocalyptic” sounds of a New Zealand band called The Dead C (and counterpoints from bands like Stereolab and the Velvet Underground). Yes, I abused my programming power to spend three hours on pretentious college radio wankery intended as a massive middle finger extended in the direction of those who wanted their Sunday Opera fix. (I’m glad to see that the station has since found DJs who enjoy opera and carry on the tradition in the proper way — but I couldn’t take it any more that summer.)

The Raw Deal was the 1992-93 incarnation of what had become a tradition of Thursday night hip-hop / house music programming (going back to the A-Team and Club Krush and Sounds of the Underground, and succeeded by Vibes and Vapors). The shows had tremendous and dedicated listenership, and we put up with a fair number of shenanigans from the rotating program participants because we wanted that music in the station’s airsound. I was already having a bad day when I learned at the last minute that none of the regular Raw Deal crew could make it to the station one Thursday. I knew that the station didn’t have enough appropriate records for me to try to cover a three-hour shift, so I went in a totally different direction — the program consisted of Michael Jackson narrating the story of “E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial.” (I think I played it twice during the three hours.) At every break, I made it clear that the usual DJs were not available, apologized for the last-minute change in programming, and tried to assure listeners that the proper show would return the following week. But the phones kept ringing all night — a few complaints and questions, a few requests that I couldn’t honor even if I’d wanted to, but the vast majority requesting “shout-outs” to their friends and families. It had never occurred to me that people would request a shout-out without also listening to the program.

One of WPRB’s great benefits and values was the ability to interact with people from outside the campus. We knew (and took it as a badge of honor) that most students didn’t care for our programming. We also had the chance to work with a wide array of local listeners who wanted to be part of the station, mostly during the summer.

George Mahlberg, more commonly known to WPRB listeners as “Dr. Cosmo; Esq.”, for instance, was a fabulously inventive person who enriched the experiences of all those lucky enough to share time with him. His signature audio sculpture on Friday evenings (10pm until he cared to turn off the transmitter) was “In-a-Gadda-da-Oswald,” a shifting and shimmering audio investigation of Iron Butterfly’s psychedelic epic, audio from the assassinations of JFK and Oswald, and whatever else crossed his synapses in the moment. I spent many Friday nights at the station, and others driving the back roads of central New Jersey, listening to his stories and rants and the connections he’d draw between seemingly disparate records.

At the mic: George Mahlberg (aka “Dr. Cosmo”)

As partially recounted on one of George’s contributions to the old WPRB History web pages (ed note: we’re slowly migrating all of them to this new site), he and I had a particularly special collaboration one night in 1994. I stopped by the station to help with the cut-over from Control A (in desperate need of renovation) to the newly-restored Control C, and George was spinning “Nocturnal Transmissions” from his makeshift home studio. I decided to have a little fun, and started playing records in the studio and mixing them with and against what George was doing at home. After a quick back-channel phone call to confirm that I was mixing live in Control C, we quickly launched into some high-wire-without-a-net stuff. Nothing was planned, and yet there was some cosmic connection that had us reaching for the same records at the same time (this was long before “computers in the studio” and instant messaging to coordinate what we were dong). At one point, we had three or four copies of “Here Come The Warm Jets” playing at different speeds and pitches (and directions)… flat out amazing. I’m still saddened that George is no longer with us, but he lives on at WPRB through the “Rock Blastaar / Dr. Cosmo” mural (see below), the plaque naming the production studio in his honor, and of course through each DJ who takes that same journey of self-discovery through the station’s immense library.

I’ve had the good fortune to remain involved with WPRB since graduating, as a board member and advisor to Princeton Broadcasting Service, Inc. It’s been exciting (and sometimes exasperating) to see the station evolve. The big steps get the most attention, such as acquisition of the Nassau Weekly arts-and-culture newspaper, the move from Holder Hall to Bloomberg Hall, or the adoption of a non-profit fundraising model. But it’s equally gratifying to see each generation of students teach itself how to operate a small business with a potential audience/customer base of over seven million people.